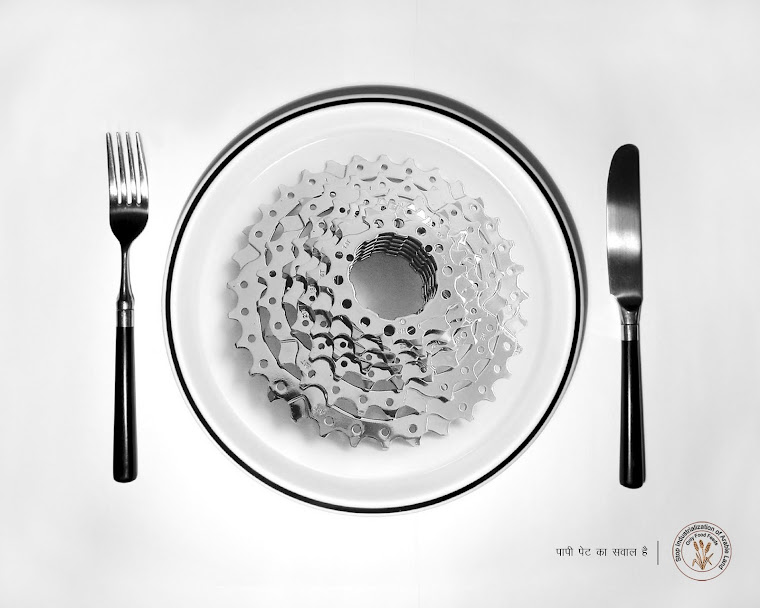

P E S S I M I S M A N D D E P R E S S I O N H A V E D E E P R O O T S I N A C O U N T R Y W H E R E S U I C I D E I S W I D E L Y R E G A R D E D A S A S O L U T I O N

Krisztina Fenyo

The tune is strangely gripping, and the lyrics capture an odd longing for death. The sad and monotonous song easily entices one into feeling depressed. It's Gloomy Sunday - the Hungarian "suicide anthem".

"Little white flowers won't wait for you, not where the black coach of sorrow has taken you. Angels have no thought of ever returning you. Would they be angry if I thought of joining you?"

A pianist today still sometimes plays Gloomy Sunday in the old popular Kis Pipa restaurant, the same place where the song's composer, Rezső Seress, used to play it in the early 1930s. Gloomy Sunday became world famous as it was sung by Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, and had versions in Swedish, Chinese, Japanese and even Esperanto.

When the song appeared it soon came to be known as the "suicide anthem" because its impact was so lethal that many people were said to commit suicide to it and leave the lyrics with their farewell letters. Later the composer himself also took his own life by jumping out of a window.

Hungarians have long had a reputation as being the gloomiest nation in Europe.

They are renowned for their pessimism, depression is a nationwide problem, and until recently they had the highest suicide rate in the world, according to the World Health Organisation. Recent surveys also show that they die earlier than most European peoples.

Gloom, depression and suicide seem to be part and parcel of Hungarian culture. "You can hardly meet with a Hungarian who wouldn't have relatives or friends who really committed suicide - it's a kind of national disease, it's a kind of sickness," says Peter Muller, a Hungarian playwright who has written a play about Gloomy Sunday and has studied the suicide phenomenon.

Suicide as a solution

In some areas in the countryside suicide is so general that no family remains unaffected. In recent years a number of small and isolated settlements in southern Hungary came to be known as 'suicide villages' as their rate is even higher than the average national figures.

Until last year there were 4,500 recorded suicides a year in Hungary, which, was the highest per population figure in the world. Not only many people kill themselves in Hungary but they also often choose brutal methods: they jump down wells, hang themselves, or drink pesticides.

Psychiatrist Dr Bela Buda says one problem is that Hungarians regard suicide in a very different way to people in other countries. "In the unconscious popular mind suicide is a positive pattern of problem solution, it's a formula which is actualised in times of crisis because everybody has experiences with other persons who committed suicide and who were regarded not as failures but as brave people daring to restore their self-esteem and dignity by this desperate and heroic act."

The sadness and gloom has a long tradition in the country's history. Many famous historical figures, from the middle ages to modern times, ended their life with suicide. The politician revered as 'The Greatest Hungarian', Istvan Szechényi killed himself, as did a wartime prime minister, Pal Teleki, as did the poet Attila Jozsef, and as did the actor Zoltan Latinovits at the very same train station where the poet threw himself in front of a train.

They were all outstanding talents and characters, but their suicides became part of what suicidologist call 'the heroisation of death'. Still today there are instances almost every year, Buda explains, of young people trying to commit suicide at the same train station where the poet and the actor had killed themselves.

According to Buda, the many historical models and their copying shows that Hungarian culture is "favouring defective, maladaptative patterns of solution for life problems". Others who have direct experience with people "in crisis" agree that suicide does seem to many Hungarians as a form of solution. A volunteer worker at an anonymous helpline phone service - where many calls are suicide related - has anwered callers for seven years.

He also feels that suicide is an accepted form to solve problems. "Somehow it is in our culture that there is way to solve a problem easily, to quit in this way," he explains, "sometimes people want to punish somebody with whom they have a difficult relationship."

Alarming mental health problems

The high rate of suicide, however, is just one symptom of the Hungarians' dire mental health, psychiatrists say. About twenty-five percent of the population suffer of anxiety illnesses, and a very large part of it coupled with depression. There is a growing number of mental disorders and the rate of alcoholism and smoking is also alarmingly high, experts say.

Hungary now leads world statistics in liver sclerosis, 8500 cases a year, an illness directly linked to alcoholism, Dr Buda says. In 1995 there were 8500 cases of liver sclerosis death, in the previous year there were 7300.

This was far the highest rate in any country in the world, according to Buda. "This dramatic elevation shows that in the last years there must have been a continuous heavy drinking in many hundreds of thousands people in Hungary".

In fact, many experts agree that behind the recent drop in suicide figures there is a growing rate of mental disorders and the growth of alcoholism. Buda says that "suicidality" itself has not decreased but merely manifests itself in alcoholism which leads to earlier death. In other words, many potential suicidal victims die before reaching the suicide age.

Life expectancy is now one of the lowest in Europe in Hungary, with the population decreasing by thirty to forty thousand every year, experts say. If this trend continues Hungary's population will fall below ten million by the next century.

Reasons and theories

Dr Buda says one reason for Hungary's disturbing mental health is the enormous social changes of the last decades, with which broke up old supporting kinship and family ties. Since the 1950s almost 60 percent of the population changed residence and social status during the process of accelerated industrialisation, Buda says. "This huge horizontal and vertical mobility meant that a lot of people became isolated, alienated, as kinship systems, family ties were destroyed," he says.

Similar changes also took place in other central and eastern European countries but in countries like Romania and the Slavic countries, the kinship and family ties remained stronger, Buda explains "What is important is that in Hungary the degree of individualisation is very high, almost as high as in the Western countries."

Indeed, Hungarians often say that they are caught in between two worlds, East and West, and feel that they are 'too western' for their geographical location. Hungary has often been compared by many writers to a ferry boat - moving between East and West, longing to anchor at the Western shore but always pushed back to the East.

"This intermediary situation is really characteristic - our short trips to the Western shores imbued as with values and aspirations, but we had to go back to our Eastern realities and if you taste something then you might begin to miss it," Buda echoes the theory.

But the Gloomy Sunday playwright Peter Muller thinks that there is more to the Hungarian gloom that just frustrated aspirations. The real reasons go much deeper, he says. It is essentially a problem of identity. "Somehow the root is missing. We live in a very strange position of the world. We always try to stick to the Western culture, we try to escape from the Eastern mentality and somehow we are in a limbo, we don't belong to anybody, it's a kind of loneliness. We have somehow lost our Oriental roots without finding another one - and if you are in trouble, if your life is difficult it is the root that can save you."

Many Hungarians, however, will insist that they are not really gloomy, let alone pessimistic. The fact that they complain readily and frequently, Dr Buda says, is merely a mechanism by which they cope with problems or try to elicit help.

And many Hungarians will also emphasise that they really are a merry people, and they point to their many humorists, cabaret figures, and their passionately merry gypsy music. Peter Muller explains this by saying that the Hungarians have an essentially antagonistic spirit, a 'double feeling' in their mentality. Beside their gloom, there is always a determinism to survive, a "but" factor, in Muller's words.

"There is always a great 'but', and this 'but' is a very Hungarian word. 'But' we have to do it, 'but' we have to survive ..... It is in the melodies, it is in the music of the great Hungarian composers - you can find a lot of 'but's in Liszt's work, in Bartok's work - they are full of such 'but's. It's a very strange and special strength beside the sadness."

No comments:

Post a Comment